Perseus of Tarsus and the Lion Headed God

Plutarch says that the origin of Mithraism was Cilician pirates encountered by the Roman general Pompey in 67 BC. These pirates:…offered strange rites of their own at Olympus, and celebrated there certain secret rites, among which those of Mithras continue to the present time, having been first instituted by them.

However, the archaeology says something just a little different: that the most important cult in Cilicia at that time was devotion to none other than Perseus. Continuing to pull on the thread, Ulansey cites the evidence from antiquity that the city of Tarsus was said to have been founded by Perseus and was named after his “swift tarsos” or foot. Coins from the city show Perseus often in association with Apollo Lykeios. This Apollo is a particular artistic representation of the god leaning on a support with his bow in his left hand and his right forearm resting on his head as if having just completed a long and difficult task.

Just as Perseus is associated with Apollo, so is Mithras closely associated with the Sun and in Mithraism, the sun is active, playing a part in the tauroctony, the sacred feast, and the ascent to heaven. Another important symbol from the coins of that locale is that of a lion attacking a bull with Perseus standing in the foreground holding his curved knife. As some scholars have suggested, it is the lion-bull combat which eventually morphed into the tauroctony scene, perhaps passing through other stages such as Perseus and the Gorgon, before becoming Perseus disguised as Mithras replacing the lion slaying the bull, all of which we recognize as typical comet disintegration scenarios told and retold and embellished through time. These have nothing to do with the constellation, Leo, which would explain why lions are not normally included in the tauroctony proper. But since lions do, very much, have to do with comets, that explains their association with Mithraism. Also, as it happens, the lion-headed god is has been found in in a cave in the Hohlenstein mountain of the Swabian alps, Germany dating as far back as 30,000 BC. After this artifact was identified, a similar, but smaller, lion-headed sculpture was found, along with other animal figures and several flutes, in another cave in the same region of Germany. This leads to the possibility that the lion-figure played an important role in the mythology of humans of the early Upper Paleolithic.[1]

Certainly, it would be a huge leap of assumption to connect this ancient lion-headed figure found in Germany to the lion-headed god of Mithraism, but Bailey, Clube and Napier have mathematically extrapolated the arrival of the Giant Comet to the inner solar system in paleolithic times, so it would simply show that different cultures at different times depicted comets in similar ways. Take Sekhmet, the lion-headed goddess of the Egyptians, for example; not to mention the war crown of the Egyptian Pharaoh which produces the effect of a flaring mane about his head, surmounted on the forehead by a cobra, snakes and dragons also being traditionally associated with comets. There is also the Ishtar gate in Babylon that was decorated with a lion, the symbol of the goddess.

[1] aurignacien.de

Porphyry wrote that the mithraeum functioned as the place of initiation into a mystery of the “descent and exit of souls” and that it was designed and equipped for this purpose as a “likeness of the universe. The things which the cave contained, by their proportionate arrangement, provided [the] symbols of the elements and climates of the cosmos.[1]

[1] De antro nympharum 6, trans. Arethusa edition. Cited by Roger Beck (2000) Ritual, Mythi, Doctrine, and Initiation in the Mysteries of Mithras: New Evidence from a Cult Vessel in The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 90, pp. 145-180.

____________________________

The Great Supper of God

If we consider the emergence of the many rites of sacrifice that appeared around the globe in association with catastrophic encounters with comets and their debris, we can understand that it was probably thought by the many peoples that suffered these encounters that the gods were either angry or hungry and thus, to attempt to prevent random destruction, would instead offer sacrifices to appease or “feed” the god. If sins had been committed bringing on the destruction, someone had to “pay” via sacrifice. Often, it was the king or leader himself who was seen as having sinned in some way leading to withdrawal of the gods’ favor or implementation of smiting, and he was then obliged to submit himself to being sacrificed or someone became a substitute for him, innocent children being among the favored candidates.There were often massive sacrificial ceremonies that took place all over the world in response to threats by comets and related astronomical and environmental phenomena: the gods “ate” the lives of the sacrificial victims. And thus, I think, the emulation of the Feast of the gods became a symbolic way of assimilating oneself to the god, acquiring his powers, or at the very least associating oneself with him/her/it as a “son” or “daughter.” One is reminded of the striking words of Jesus: “Take, eat, this is my body broken for thee” and “Take, drink, this is my blood shed for thee”. This, of course, takes us dangerously close to human sacrifice and cannibalism. As we’ve already seen, cannibalism was often associated with post-cataclysmic recovery but I don’t think that’s what is indicated here. Rather, it reminds me of “The Great Supper of God” in the New Testament book, Revelation, which is loaded with cometary imagery:

Then [the angel] said to me, Write this down: Blessed are those who are summoned to the marriage supper of the Lamb. And he said to me [further], These are the true words (the genuine and exact declarations) of God. ….

After that I saw heaven opened, and behold, a white horse [appeared]! The One Who was riding it is called Faithful and True, and He passes judgment and wages war in righteousness. His eyes [blaze] like a flame of fire, and on His head are many kingly crowns; and He has a title inscribed which He alone knows or can understand. He is dressed in a robe dyed by dipping in blood, and the title by which He is called is The Word of God. And the troops of heaven, clothed in fine linen, dazzling and clean, followed Him on white horses. From His mouth goes forth a sharp sword with which He can smite (afflict, strike) the nations; and He will shepherd and control them with a staff (scepter, rod) of iron. He will tread the winepress of the fierceness of the wrath and indignation of God the All-Ruler. And on His garment (robe) and on His thigh He has a name (title) inscribed, KING OF KINGS AND LORD OF LORDS.

Then I saw a single angel stationed in the sun's light, and with a mighty voice he shouted to all the birds that fly across the sky, Come, gather yourselves together for the great supper of God. That you may feast on the flesh of rulers, the flesh of generals and captains, the flesh of powerful and mighty men, the flesh of horses and their riders, and the flesh of all humanity, both free and slave, both small and great!

Then I saw the beast and the rulers and leaders of the earth with their troops mustered to go into battle and make war against Him Who is mounted on the horse and against His troops. And the beast was seized and overpowered, and with him the false prophet who in his presence had worked wonders and performed miracles by which he led astray those who had accepted or permitted to be placed upon them the stamp (mark) of the beast and those who paid homage and gave divine honors to his statue. Both of them were hurled alive into the fiery lake that burns and blazes with brimstone.

And the rest were killed with the sword that issues from the mouth of Him Who is mounted on the horse, and all the birds fed ravenously and glutted themselves with their flesh. [1]

Nice imagery, eh? Gives an all-new meaning to “The Last Supper”, yes? Reminds me of that great scene in Tennessee William’s play, Suddenly, Last Summer, where Violet Venable recounts how her son, Sebastian, was watching hatching sea-turtles being devoured by birds of prey and claimed, when the feeding frenzy was over that at last, he had seen God. Maybe he was more right than most of us suspect.

If there had been more than one comet in the skies at some point in the past (which is likely according to the science) and there was possibly an encounter, or simply that one of them broke into many pieces and rained chunks and ferruginous material on the earth, red comet dust mixed with rain, it would indeed seem that the god had sacrificed himself – or had been killed or sacrificed in an encounter with another comet-god who had assumed the role of protector as we have seen in the myths. The saving cometary body, would then depart, the sun would return to the dust shrouded earth, and it would be thought that the gods had “feasted” – perhaps on the disintegrated comet body as much as on the deaths of human beings - and been satisfied. Thus, the feast symbolized the departure of the danger and the return to life.

Christianity, on the other hand, brought the event down to earth, historicized it and made human beings responsible for the death of the god-man whose sacrifice (I’ll let you kill me for your sake!) saved them from “sins” which would ultimately allow them to “go to heaven”. This is an example of the “astralizing” effect of the Greek philosophers trying to figure out what certain stories and myths about gods in the skies could have meant in times when the sources of those stories had disappeared from the skies. Christianity, too, arose out of cataclysms: the collapse of the Roman Empire and the subsequent dark age, and its terms were designed to deflect blame away from the ruling hierarchies by granting the promise of a future life in paradise as long as people could endure whatever troubles assailed them on earth with patience and fortitude – including comets, earthquakes, famine, plague, and the rest of the cocktail of god’s wrath they were intended to imbibe and be thankful for being allowed to do so. But that was to come later.

Looking at the “ symbols of the elements and climates of the cosmos” mentioned by Porphyry, we are reminded that the “climate” of the cosmos is how the ancients thought about comets; after all, Aristotle’s Meteorologica was mainly about explaining away the “cosmic weather.”

Water From Rocks and the Word of God

Classicist, Roger Beck, mentioned above, wrote an interesting article on a cup found in a Mainz mithraeum which he speculated represented initiatory activities in its decorations. The vessel is dated to the first quarter of the 2nd century[2] and is among the earliest pieces of evidence for the Mithras cult on the Rhine Frontier. He argued that each of the two scenes represent the performance of a ritual. What caught my attention was that one of the scenes is supposedly an initiation where the person in the rank of the Father, wearing the Phrygian cap, is in the act of drawing a bow and aiming the arrow straight at the naked figure in front of him, the person being initiated. A third figure is present making a hand gesture with thumb and two fingers (index and middle) extended and the other two fingers folded over the palm. Beck proposes that the activity is designed to convey information on more than one level. In the first place, it is a reenactment of a cult myth that is found in many side scenes in mithraea, something called the “water miracle” where Mithras shoots an arrow at a rock to draw water from it. On another level, it is designed to induce in the initiate a certain state or, at least, represent his passage from one state to another by means of having received certain teachings. The third level was that the performance of the ritual would act as a form of sympathetic magic and change the conditions of the present environment as the conditions of the environment had been changed in the past by the actions of the god.…the mythic event of the water miracle is replicated in ritual, as a rite of initiation, by the feigned archery of the Father, just as the banquet of Mithras and Sol is replicated by the banquet of the initiates presided over by the Father and the Sun-Runner. … why should the water miracle be chosen as the archetype for an initiation ritual: With the banquet the question scarcely arises; that the celebration of man should replicate the celebration of gods is self-evidently appropriate. The relevance of Mithras’ archery to initiation, however, is not so obvious. …

Scholars, however, are unanimous in the following reading: Mithras shoots at a rock and elicits water from it; the other figures in the scene (sometimes one, sometimes two) serve either to petition Mithras or to receive gratefully (sometimes in cupped hands) the gushing water. The archery is thus interpreted as a victory over drought, an action once performed by the god in mythic time to relieve world-wide aridity and thus performable again in actual time at the behest of his devotees.

…a ritual of initiation that replicates the water miracle is admission into that more abundant life symbolized by the waters elicited by Mithras the bowman. …archery thus becomes a mode of baptism.[3]

That no questions are raised about the banquet is surprising considering the extract from Revelation, above, and what a gods’ banquet might actually be. As for the interesting hand gesture, it has been studied extensively by various scholars and apparently indicates “the presentation of reason through language,” i.e. that something is being spoken during the initiation that carries some weight or that teachings have been given that have led to this initiatory moment. But, what strikes me the most about this event attributed to Mithras is that, once again, we have a correspondence to Moses in the desert striking the rock for water during the protracted, 40 year, Exodus. There were actually two water miracles of Moses: in the first case,[4] he was instructed to strike the rock with his staff; he did and water flowed. In the second instance, 40 years later, he was told to just speak to the rock.[5] But he didn’t, he struck it instead and nothing happened. Then he hit the rock a second time, and finally the water came. It is said that it was for this lack of following instructions exactly, or lack of faith, that Moses was denied entry to the Promised Land which seems pretty harsh to me. Naturally, there’s a whole lot of mental gymnastics that gets performed explaining that nonsense, but what is important is that we are seeing here, instances where striking a rock (or initiate) for water and speaking to a rock (or initiate) are related to each other in a peculiar way. It is as though there is a dual emphasis on action and word that can be done and spoken to re-invigorate or replicate the miracle of getting water from a rock or achieving abundant life; the right ritual, the correct behavior, can align one with the powers of the god. Perhaps the ritual was as simple as reciting the story of the event while it was being re-enacted, or saying the correct words that were alleged to have been spoken by the god at the time; it could have been as complex as a long period of instruction and efforts to achieve self-knowledge before initiation was performed.

Well, that’s the astral religion angle. What about the cometary angle? Could the arrow represent a thunderbolt, as in an electrical discharge that split a rock and water burst forth? A thunderbolt is accompanied by a tremendous crashing sound, i.e. “the voice of god”, so perhaps the comet Moses had lost his vigor after 40 years?

There is another series of interesting connections to this idea of stones releasing water though it is combined with stones that also stop water, and stones with symbols of gods graven on them thus giving them power, possibly the power of “the word”. So, let us make a somewhat deeper digression that will bring a number of elements to light.

Ulansey conjectures that the influence of Aratus in Tarsus may have led to the emphasis on astrology within the Stoic movement. It could very well be that it was from Eudoxus’ 3000 year old astronomical knowledge, combined with the works of Pherecydes and Pythagorus, that the tauroctony of the Mithraic Mysteries derived. But there is more to it than that: in case you didn’t notice, the figures in the tauroctony are reversed from the way they actually appear in the sky. Ulansey proposes:

…on ancient (and modern) star-globes (like the famous ancient “Atlas Farnese” globe) Taurus is always depicted facing to the right exactly like the bull in the tauroctony. This shows that the Mithraic bull is meant to represent the constellation Taurus as seen from outside the cosmos, i.e. from the “hypercosmic” perspective…[6]

Yet we know, for a certainty, that the particular time is important, as I said, from my own arrival at that date via a different path, as well as Ulansey’s interpretation of the equinoxes being delimited via the figures Cautes and Cautopates.

[1] Rev 19:9 – 21, Amplified, Zondervan.

[2] Wetterau ware.

[3] Beck (2000), p 151 – 153, excerpts.

[4] Exodus 17:6

[5] Numbers 19:1-22:1 - 20:8

[6] David Ulansey (19914) Mithras and the Hypercosmic Sun, in Studies in Mithraism, John R. Hinnels, ed., Rome.

___________________________________

Hipparchus is central to Ulansey’s theory that precession of the equinoxes was the great secret of the Mystery cult. There is no known connection between Hipparchus and the Stoics except for the fact that he lived at Rhodes and so did Panaetius and Posidonius.

Perhaps the “weighty words” being indicated in the ritual enactment on the Mainz vessel, as well as the word that Moses should have spoken to the rock to produce water, was the “name of the god”? That does seem to be what is indicated by the “Seal of Solomon”, i.e. the Mâgên Dâwîd, being inscribed on the stone that was throne into the well by David.

What was this cult talking about or doing that made it spread and persist the way it did? Why did the emperors of the Roman empire, in 308 AD set up an altar, offer a sacrifice, and repair a mithraeum in Carnuntum in the midst of a crisis when the empire was actually threatened by civil war? And did their participation in the cult of Mithras have anything to do with their actions as emperors? If so, what did that cult teach them? What did they know?

We’ve already learned that Plutarch traced the origin of the Cult of Mithras to Cilician pirates, and Ulansey has revealed that the city of Tarsus there was devoted to Perseus and that there are coins and other artifacts to confirm the relationship. He bases his argument on the fact that there are three kinds of evidence: 1) astronomical consisting in the fact that Perseus occupies a position in the sky analogous to the position of Mithras vis a vis the bull he is slaying. 2) the striking iconographical and mythological parallels between the two figures; 3) the historical and geographical evidence linking the origins of the cult to Cilicia, the site of the Perseus cult.

Okay, I buy it to some extent. What troubles me is the lack of evidence that the Mysteries of Mithras were significant in the Eastern areas surrounding the proposed birthplace. As we have already noted, the concentration of archaeological finds are focused mainly on Germany, Pannonia and Italy. We have also noted in passing, the presence of a lion-headed god figure in Germany back in Paleolithic times, though we can’t propose a connection over that vast a period of time. The similarities between the Babylonian gods, the Phoenician gods, the Jewish-Muslim god-models for David, Solomon and Moses, and Perseus-Mithras are striking.

Ulansey continues his interpretation rather promisingly by saying “since it was astronomical considerations which led us to connect Mithras and Perseus in the first place, it stands to reason that the origins and meaning of that connection must be sought in the context of Mithraic astronomical symbolism.”[1] He then begins to build his argument on the ideas of Beck and Insler, that the constellations represented in the tauroctony are those along the ecliptic at the time of the setting of Taurus in the Spring, that is a sky map that represents how the sky looked at a particular time which the Mithraists wished to commemorate. However, it was apparent that the constellations don’t exactly match up with the zodiac which lie along the ecliptic.

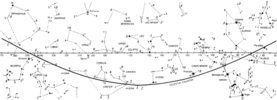

The next idea presented by Ulansey is that of Michael Speidel who argued that the constellations depicted are the ones along the celestial equator rather than the ecliptic. That actually worked. The problem there is that, during Graeco-Roman times, Aries and Libra marked the equinoxes – the points where the celestial equator and the ecliptic cross in spring and autumn - and were thus the two most important equatorial constellations; yet they are not indicated at all, in any way, in the tauroctony. Nevertheless, Ulansey’s realized that the particular constellations would fit exactly if you move the clock back to the time when the equinoxes were in Taurus and Scorpio. Here is a small version of Ulansey’s star map showing the result of doing just that.

[1] Ulansey, op. cit., p. 45.

_____________________

The celestial equator (line curving down) with the Spring Equinox in Taurus.

As you see, Perseus, in the upper right, is just above the celestial equator at this moment. Looking at this image for a bit, and playing with the Starry Night program to get the one on my screen to match it revealed that this map shows the spring sky just before dawn about 3000BC at a latitude of about 43° N. That date got my attention because in my book, Secret History, I had proposed a similar date for an event involving the constellation, Taurus, though I had arrived at it from a very different angle following very different clues. The convergence of the result of these two paths was quite startling. Before I compare the two, let’s just continue with Ulansey’s argument.

Ulansey was able to figure out the clues because he knew about the precession of the zodiac so he wondered if the tauroctony scene really did exhibit knowledge of the precession? As he demonstrates, the celestial equator, rather than the ecliptic reveals exactly the series of figures contained within the tauroctony with Taurus at the setting end and Scorpius rising in the east, and the two of them framing Canis Minor, Hydra, Crater, and Corvus: the dog, the serpent, the cup and the raven. So, our intrepid researcher followed the clue of the celestial equator.

Ulansey brings our attention to the fact that the symbol of the cross may actually come from the image of the celestial equator crossing the ecliptic twice a year. In Plato’s Timaeus, we are told how the creator of the universe constructed it out of two circles that were joined “in the form of the letter X”. An example of that is revealed in an early Mithraic monument which shows the Lion-headed god standing on a globe crossed by an X.

However, crosses were revered long before Plato and it was only about 600 AD that the Catholic Church adopted it as the symbol of Christianity; before that, there was the fish. Nevertheless, knowing that there was a “crossing point” where the track of the sun crossed a certain boundary could have been known to the ancients and important, at the very least, as a marker of seasons. But precession of the equinoxes is something else altogether, it is the knowledge of a slow movement of the equinoctial points backward through the zodiac over very, very, long periods of time, like 26,000 years! It is theorized to be due to the earth itself performing a long, slow “wobble” where the north pole of our planet “bows” in a slow, graceful motion like the axis of a spinning top (Newton’s explanation). Of course, when you are observing a spinning top and this slow wobble, you notice that, as the speed of the spinning slows down, the wobble becomes more pronounced until the bowing causes the top to just falls over. Planets don’t do that because they are spinning for reasons other than someone winding them up but it is thought that the same principle applies. I’m not too sure about that myself because I have read more elegant and reasonable explanations for precession such as the proposition that it is due to the entire solar system’s curvilinear motion through space along with the galaxy of which it is a member.[1] But whatever the cause, did whoever create the iconography of the Mithraic mysteries know about precession?

[1] W. E. Glanville, (1918) A Possible Relation between Equinoctial Precession and the Sun’s Motion in Space; Comet and Asteroid Notes, Maria Mitchell Observatory, NASA Astrophysics Data System.

_____________________________

Obviously the ancient peoples were aware of the equinoxes themselves simply by watching the sunrise and sunset every day. The great megalithic astronomical observatories, such as Stonehenge, give evidence of this fact. It’s one thing to notice that the sun and zodiac move up and down in relation to the earth and its supposedly fixed position in relation to the fixed stars, and to make note of that point in each year when the sun is at the mid-points, crossing in the spring and autumn, the high point in summer, and the low point in winter. It is quite another to know that this process includes a slow backward movement of that point where the ecliptic and celestial equator meet.

Obviously the ancient peoples were aware of the equinoxes themselves simply by watching the sunrise and sunset every day. The great megalithic astronomical observatories, such as Stonehenge, give evidence of this fact. It’s one thing to notice that the sun and zodiac move up and down in relation to the earth and its supposedly fixed position in relation to the fixed stars, and to make note of that point in each year when the sun is at the mid-points, crossing in the spring and autumn, the high point in summer, and the low point in winter. It is quite another to know that this process includes a slow backward movement of that point where the ecliptic and celestial equator meet. But it is certain, from Ulansey’s analysis, that the tauroctony did, indeed, represent a view of the sky when the equinoxes were in Taurus and Scorpio.

Putting the torchbearers as equinoxes together with the creatures depicted in the scene, confirms Ulansey’s idea that the tauroctony is an image of constellations along the celestial equator at a particular moment in time. He must have also realized that the only period in time when this could have been the image of the night sky just before dawn was over 5000 years ago!

Ulansey’s collecting and connecting of the clues is a brilliant piece of detective work. Figuring out that Mithras is identical to Perseus, locating the cult of Perseus in Tarsus right where the Cilician pirates were based, figuring out the role of the torchbearers as symbols of the equinoxes, and putting that together with the work of previous researchers regarding the sky map is marvelous. He next seeks out the clues regarding who knew about precession, and when, and comes across the interesting fact that the discoverer was associated with the Stoic philosophical school, and that Tarsus, where the Perseus cult was thriving, was a veritable hothouse of Stoics. More than that, the whole scenario of connections just happens to coincide with the time period that Plutarch assigns to the emergence of the Mithras-worshipping pirates. That, of course, is what led him to his idea: that the important thing being conveyed in the tauroctony was the fact that the equinoxes precess, that this was the “great secret”, a new and worshipful cosmic force: the Dreaded Precession! He argues that:

…the god Mithras originated as the personification of the force responsible for the newly discovered cosmic phenomenon of the precession of the equinoxes. Since from the geocentric perspective the precession appears to be a movement of the entire cosmic sphere, the force responsible for it most likely would have been understood as being “hypercosmic,” beyond or outside of the cosmos…. Mithras, as a result of his being imagined as a hypercosmic entity, became identified with the Platonic “hypercosmic sun,” thus opening up the way for the puzzling existence of two “suns” in Mithraic ideology.[1]

There are, however, a few problems with this theory not the least of which is the fact that I came to the conclusion that the date in question was very important to the ancients by a singularly different route and chain of clues and discussed it in my book, Secret History. My theory of what the date signified wasn’t much more interesting than Ulansey’s because I didn’t then have the knowledge of cometary disasters as theorized by the numerous scientists whose work I have cited in the previous volume at that time. Indeed, I related the date in question to cataclysmic events involving clusters of comets in a certain sense, but without the refinements that are now possible with the added science on the table.

[1] David Ulansey (1994) Mithras and the Hypercosmic Sun; Studies in Mithraism, John R. Hinnels, ed. L’Erma di Brettshneider, Rome, pp. 257-64.

Regarding Ulansey’s conclusion to his wonderful exposition of the evidence, all I can say is that he is a true Platonic “astralizer”.

First of all, just because a scene depicts a specific moment in time over 5000 years ago, does not mean it is a projection backward by someone who figured out precession of the equinoxes. But if it were merely a re-working of more ancient material, where are the antecedents that would suggest the things that have been included in the scene? They could have existed at the time, of course, since so much has been lost. What is most interesting about the tauroctony is how it incorporates elements from a wide variety of what appear to have been Mesopotamian myths. It’s like a hybrid determined to not be misunderstood and I suspect that there was a very serious reason for this because, certainly, there was no need to create a mystery religion around precession. The knowledge about precession was not being hidden and there is no reason that it could not be openly discussed in the various philosophical schools that existed at the time. What is more, the idea that it is focused on a “hypercosmic sun” is way too Platonic and not enough Stoical to pass muster.

But still, there is the fact that whoever came up with this hybrid mystery cult most certainly did intend for the information about the equinoxes to carry weight and, more than anything else, that suggests that it was recording an event of extreme importance, a date. Because, in point of fact, that was what the Babylonians used “astrology” for in the beginning: as a means of recording time. So, my suggestion is that someone had access to certain information gained from studying ancient texts. That information was supplemented by the discovery that the equinox precesses. Perhaps understanding of precession enabled that person to figure out something very important from those texts, including a date. Were they then able, utilizing their knowledge of astronomy, able to re-create the night sky in images by precessing the sky map? Another question that this raises is: did the person who figured out the code from more ancient sources also figure out that such an event was in the future and was the tauroctony not just a record of the past, but a warning for the future? That sort of thing would truly be worthy of creating a new mystery religion. But that is just speculation.

So the question for us here is this: if the tauroctony of the Mithraic Mysteries was a record of a cataclysmic event – the very event that I dated in Secret History via a different pathway - did the person or persons who either created or modified and propagated this cult know about the event in any detail? Did they also, in the process of accessing the records and knowledge from which they constructed their hybrid cult, also discover a method of prediction, and formulate a theory about amelioration? And finally, was this information known to the Roman Emperors, Diocletian, Maximian, Constantius Chlorus and possibly Galerius and Constantine?