Chapter 20 (2nd part)

Charlemagne

As we have seen the people far enough from conflagration survived (for example Scandinavia, Great Britain, Eastern Europe, Near East, Spain) and, in some cases, prospered and spread Paleochristianity.

Meanwhile, Western Europe was a pile of rubbles. After more than two centuries of survival and stagnation, after the last plague outbreak, Western Europe re-emerged around 750 AD. But

Paleochristianity as preserved by surviving populations was way different from official Christianity or Roman Christianity as spread, centuries later, by Charlemagne. This period of is called the Carolingian Renaissance:

During this period, there was an increase of literature, writing, the arts, architecture, jurisprudence,

liturgical reforms, and scriptural studies.

[1]

Notice the two last items: liturgical reforms and scriptural studies, does it suggest some kind of heresy? Most specifically, the most salient effect of the Carolingian Renaissance was a

moral regeneration:

[The Carolingian Renaissance] had a spectacular effect on education and culture in Francia, a debatable effect on artistic endeavors, and an unmeasurable effect on what mattered most to the Carolingians, the

moral regeneration of society.

[2]

Regeneration implies degeneration. What is the part of the society did the Carolingians consider as degenerate?

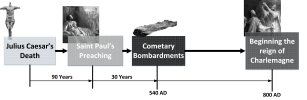

Remember that about 460 years added the official chronology? Coincidently or not, this time difference occurs elsewhere: the reign of

Charlemagne[3] began in 768 AD, and the reign of

Constantine began in 306 AD

[4]. The difference between those two dates is 462 years, pretty close to the hypothesized added years.

Actually, the alluded moral regeneration that marked the Carolingian Renaissance was centered on

Roman Christianity in general and on

Constantine in particular:

This revival

used Constantine's Christian empire as its model, which flourished between 306 and 337. Constantine was the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity and left behind an impressive legacy of military strength and artistic patronage

[5]

Charlemagne saw himself as the new Constantine and instigated this revival by writing his Admonitio generalis (789) and Epistola de litteris colendis (c.794-797). In the Admonitio generalis, Charlemagne legislates

church reform, which

he believes will make his subjects more moral and in the Epistola de litteris colendis, a letter to Abbot Baugulf of Fulda, he outlines his intentions for

cultural reform.

[6]

“Church reform”, “make his subjects more moral”, again we wonder about what kind of heresy was Charlemagne trying to eradicate?

A number of authors, among them

Heribert Illig and

Gerhard Anwander[7], doubt the historicity of

Charlemagne and argue that he was a mythical figure modeled after historical

Constantine.

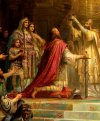

Constantine and Charlemagne on Cologne Cathédral

Constantine and Charlemagne on Cologne Cathédral

This makes sense since more or less 300 years were blank. But as demonstrated by

Ward Perkins[8],

blank doesn’t mean added.

Might it in fact be other way around: was a mythical

Constantine modeled after the historical figure of

Charlemagne? Another piece of evidence supporting this hypothesis is the forgery of the

Constantine donation:

Valla showed that the document could not possibly have been written in the historical era of Constantine (4th Century) because its vernacular style dated conclusively to a later era (8th Century). One of Valla's reasons was that Mantis Gräfelfing.

[9]

In other words,

Constantine’s legacy was to grant supreme temporal and spiritual power to the Church, and its main proof was a forgery (probably conducted at the behest of

Pepin Le Bref[10], the father of

Charlemagne).

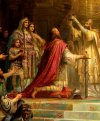

If it was not enough, according to the official narrative, Charlemagne was

crowned Emperor of the Romans by Pope Leo III in 800 AD on Christmas Day[11].

800 years, day for day, after the alleged birth of Jesus Christ. The legacy of Jesus Christ to Charlemagne and his collusion with the papacy could not be clearer.

© Friedrich Kaulbach, 1861

Imperial Coronation of Charlemagne, on December 25th, 800 AD

Charlemagne’s reign (768-814) was one of almost continuous warfare

[12]. Coincidently or not, virtually all wars directed by Charlemagne were waged against people embracing Paleochristianity:

Was Charlemagne wagging theological wars against what he considered as heathen’s beliefs? Was he imposing the law (ancient testament) where love (message of St Paul) and Mercy (Message of Julius Caesar) prevailed until then?

This is what is strongly suggested by to following passage. One thing is sure, Charlemagne acted as

inquisitor maximus before the times, waged the first Crusades imposing Roman Christianity upon dissenters:

Charlemagne wanted to act like a true king of Israel. The Amalekites had dared raise their hand to betray God’s people, and

it was therefore right that every last one of them should be exterminated. Jericho was taken and

all those inside had to be put to the sword, including men, women, old people, and children, even the oxen, sheep, and donkeys, so that no trace would be left of them. After defeating the Moabites,

David, with whom Charles liked to compare himself, had the prisoners stretch out on the ground, and two out of three were killed. This, too, was part of the Old Testament from which the king drew inspiration, and it is difficult not to discern a practical and cruelly coherent application of that model in the massacre of Verden.

[13]

Indeed, the atrocities committed by Charlemagne were waged in the name of “the laws and man” and it comes from the very own words of Charlemagne’s friend and biographer Einhard:

No war ever undertaken by the

Frankish people was more prolonged, more full of atrocities or more demanding of effort. The Saxons, like almost all the peoples living in Germany, are ferocious by nature. They are much given to devil worship and

they are hostile to our religion. They think it no dishonor to violate and transgress the

laws of God and man.

[14]

Here an extensive list

[15] of the Charlemagne’s wars, there are a lot, and coincidently or not,

virtually all his wars were directed at people embracing Paleochristianity:

Aquitaine war (778)

The first war waged by Charlemagne but not the last. Aquitaine was stronghold of Catharism. The Cathars are attested in written form as far back as 8th century AD

[16]:

© Military Wiki

© Military Wiki

Spread of the “heretics” movements

The capitulary

[17] includes several chapters that speak to a land ravaged by war. “[

T]hose churches of God which have been abandoned are to be restored” […] “bishops, abbots and abbesses are to live under a holy rule”… The region must have been ruined. To begin to rebuild,

Charles [Charlemagne] reiterated the rule of law, a theme he would return to again and again during his rule.[18]

Lombardy wars Conquest of Lombardy (773-774), Lombardy Rebellion (776), Lombard War (780) Beneventian War (787), Second Beneventian War (792-?)

Lombardy was a stronghold of the Bogomile /Cathars. Their doctrines have numerous resemblances to those of the the Paulicians, who influenced them, as well as the earlier Marcionites, who were found in the same areas as the Paulicians.

[19]

The Paulicians are attested as far back as 660 AD

[20]. It predates Charlemagne by at least one century.

Saxon Wars (771-804)

The longest and bloodiest war waged by Charlemagne. It’s during the Saxon Wars that Charlemagne perpetrated the massacre of Verden. As mentioned earlier, the Saxons held some form of Paleochristianity as early as the late-6th century.

Notice that, although being Christianized way before the Franks, the biographer of Charlemagne didn’t hesitate to demonize them:

The Saxons, like almost all the peoples living in Germany

, are ferocious by nature. They are much given to devil worship and they are hostile to our religion. They think it no dishonor to violate and transgress the laws of God and man.

[21]

Spanish wars (777-778), (779-812)

Was it only the Moors who were the targets of Charlemagne’s ire? One of main battles was located in Pyrenees, at the Roncevaux Pass, It opposed the Basques (Vascones) army - not the Muslims - to the Frankish army

[22].

Interestingly, the Basques were first Christianized by Saxons and not by the Franks:

The Basques […] were

Christianized at a par with the Germanic peoples hostile to Carolingian expansion (8th-9th century), such as the Saxons

[23]

Notice also that the Vascones’ territory extended from the Atlantic Ocean, the Garonne River, one of the hotbeds of Catharism up until the 14th Century.

Breton War (786)

Britany was Christianized as early the 5th centuries by monks from Ireland

[24] and we know that Ireland was one of the locations of Paleochristianity.

Bavarian War (787-788)

Bavaria was Christianized at latest during 7th Century

[25] which predates Charlemagne by at least 100 years. Bavaria was one of the locations of “heresies” as indicated by the map above.

Vikings War (late 700’s)

The monastery was plundered and burned, while monks were either killed or enslaved. The Vikings began attacks along the North coast of France. Charlemagne, king of the Franks, set up a series of defenses along the coast to ward off these Viking raids.

[26]

The Barbarian narrative doesn’t hold scrutiny

[27]. If the Vikings were not barbarians but civilized Paleochristian people, what was the reason behind for the raids of monasteries?

Many of the earliest recording Viking raids targeted British monasteries. Some historians argue that it was revenge against the invasion of Christianity into Scandinavia that motivated these attacks

[28]

Various reasons are ascribed by to Vikings for targeting monasteries. The odd thing is that all the invoked reasons ignore an obvious fact, the monasteries, especially at the time, were first and foremost,

the only places where manuscripts were being written, revised and copied.

So were that Vikings raid targeting monasteries motivated by looting riches and gold as generally claimed and/or were these raids motivated by more theological reasons,

indicating a struggle between Paleochristianity as held by the Vikings and Roman Christianity as proselytized by Charlemagne?

Avar War (791-796)

The Avars

[29] were introduced to

Orthodox Christianity as far back as the 5th century

[30]. The Avars lived in what is today Hungary, where was founded Bogomilism

[31].

Slavic War (798)

As seen above the Slavs were Christianized as early as the 6th century.

Croatian War (799-803)

The naval battle of opposing Julius Caesar to Pompeii took place around Taurus Island, Croatia

[32]. As indicated in the map above Croatia was one major location of Bogomilism, which survived in Croatia, at least, until the 14th century as attested by this tombstone:

© Croatian School

Bogomil tombstone in Croatia, 14th-15th century

(801-810)

Byzantium was the capital of orthodox Christianity, whose major bone of contention with Roman Christianity was the calculation of the spring equinox (more on this topic soon).

Danish War (808-810)

The Danes and the Saxons were allies. Charlemagne waged war with the Danes, who had given aid and asylum to the

Saxon leader Widukind in the Saxon Wars.

[33]

Bohemian War (805-806)

[34]

A noted for the Slavs region, the Christianization started, at the latest, during the 7th century:

At first,

the Christian rite in Bohemia was the Slavic one of the Eastern Orthodox Church, but it was soon replaced by the Roman Catholic rite, introduced due to Western influences

[35]

Controversies about spring equinox and Christmas

In a small Spanish village called Bercianos de Aliste survives a most peculiar tradition:

It is well-known that the Semana Santa always reaches its climax on Good Friday, and that most traditional Christians view the processions on Holy Saturday and Easter Sunday (Resurrectio) as merely an appendix. This would be a strange attitude, since the Resurrection—which Easter is all about—is said to occur on Sunday, not on Friday. So there seem to be two chronologies at work here, the one by the book ending on Sunday, and the underlying, but apparently traditional and more ancient chronology with

Christ’s death on Wednesday, his subsequent enshrinement, and the climax on Good Friday. This alternate liturgical current obviously ignores the events in the Passion narrative of the Gospel, where Christ is commonly believed to die on the Cross.

[36]

Easter predates Roman Christianity

[37], could it date back to the celebration of the Ides of March - Julius Caesar’s death and resurrection three days later?

This two-day offset would makes sense if one considers the original underlying chronology which is based directly on the Caesarian tradition: Caesar’s death was on a Wednesday, funeral with presentation of the effigy/crucifix on Friday.

Still today orthodox Christians have a different method of calculating the spring equinox

[38] based in the Julian calendar, the calendar invented by Julius Caesar. In orthodox tradition, Holy Unction (Caesar’s death) is a Wednesday

[39] and Good Friday is a Friday

[40] (Caesar’s resurrection).

A similar controversy exists for the celebration of Christmas. Notice that like Easter, Christmas is a tradition that predates Roman Christianity. Already, the Romans celebrated the

December 25th because it was the date of the festival of Sol Invictus[41].

Sol invictus was the official God of the late Roman Empire and the

patron of Roman Soldiers[42]. Statues were set up to Julius Caesar himself, as Sol Invictus

[43].

There no mention of the Jesus Christ’s date of birth in any of the Gospels. The earliest dating of Christmas was done in 192 AD:

Writing shortly after the assassination of Commodus on December 31, AD 192,

Clement of Alexandria provides the earliest documented dates for the Nativity. One hundred ninety-four years, one month, and thirteen days, he says, had elapsed since then, which corresponds to a birth date of November 18 or, if the forty-nine intercalary days missing from the Alexandrian calendar are added, January 6. Moreover, "There are those who have determined not only the year of our Lord's birth, but also the day" (Stromata, I.21), including dates in April and May, as well as another day in January.

[44]

Julius Caesar was born on the 12th July

[45]. Coincidently or not still nowadays, a small village in Italy celebrates Christmas on the 12th July:

Christmas in Ossola is celebrated in July. For four centuries Vagna, a very small hamlet of Domodossola (Vco), has celebrated the Feast of the Child, a rite spread in the fifteenth century by the Franciscan San Bernardino da Siena who also found roots here[…]The

appointment this year is for July 12. The climax of the feast, which lasts three days, is the solemn Sunday Mass with Christmas carols and the procession dül Bambin which sees the carrying statue of the Child Jesus, a work made in 1730 by the local sculptor Bartolomeo Zanini Piroia.

[46]

Are the controversies and remaining traditions about spring equinox and winter solstice an indication that Roman Christianity replaced Julius Caesar by Jesus Christ? Was the latter being modeled after the former?

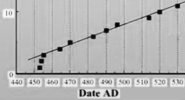

© Baillie

Irish Church foundations indicating a huge pulse in 540 AD

Notice the surge in “church” foundation ca. 540 AD in Ireland. The signs were here, comets and plagues. Extra devotion was being displayed by survivors. But was this huge spike in churches building the sole result of harsh times? In a time of bare survival for many, some people build churches in troves.

Did the plague of Justinian virus play a role too?

Why, during the time of Saint Paul, did Paleochristianity not really catch on? In almost 30 years (29 AD – 55 AD) of preaching, Paul gathered at most one thousand followers

[47]. Julius Caesar’s cult was initially circumscribed to some of its soldiers and yet, just a few decades later, Paleochristianity had taken the periphery of Western Europe by storm.

In addition, as noted above, the central values at the core of Paleochristianity –

mercy, forgiveness and love – were so foreign at the time

[48]. Another major innovation was the introduction of monotheism in a world dominated for millennia by polytheism.

Might it be that the collective trauma of cometary bombardment and/or a newly introduced virus triggered this civilizational leap?

[1] Wikipedia contributors (2021) ‘’Carolingian Renaissance’’

Wikipedia

[2] Contreni, John G. (1984) "The Carolingian Renaissance"

Cambridge University Press

[3] Wikipedia contributors (2021) “Charlemagne” Wikipedia

[4] Mark, J. J. (2019) “Donation of Constantine”

World History Encyclopedia

[5] Nancy Ross (2021) “Carolingian art, an introduction”

Khan Academy

[6] Ibid

[7] Heribert Illig

et al. (2002) “Bayern in der Phantomzeit. Archäologie widerlegt Urkunden des frühen Mittelalters”

Mantis Gräfelfing

[8] See previous subchapter “Conditions before the Plague of Justinian”

[9] Jeremy Norman (2021) “Lorenzo Valla Proves that the Donation of Constantine is a Forgery”

History Of Information

[10] Ross, 2021

[11] Barraclough, G. (2022) “Holy Roman Empire”

Encyclopedia Britannica

[12] Editors of medievalists (2022) “Was Charlemagne a Mass Murderer?”

Medievalists

[13] Ibid

[14] Ibid

[15] Editors of History Guy (2022) “Charlemagne, King of the Franks”

History Guy

[16] Philip Schaff

et al. (1994) “Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers”

Hendrickson Publishers

[17] A royal command

[18] Bentonian (2016) “769: Charlemagne’s first battle”

The Eighth Century and All That

[19] Wikipedia contributors (2022) “Catharism”

Wikipedia

[20] Editors of the Encyclopedia (1911) “Paulicians"

Catholic Encyclopedia

[21] Editors of medievalists (2022) “Was Charlemagne a Mass Murderer?”

Medievalists

[22] Editors of the Encyclopedia (2022) ‘’Battle of Roncevaux Pass’’

DBpedia

[23] Wikipedia contributors (2022) “History of the Basques”

Wikipedia

[24] Editors de Landenweb (2022) “Brittany – Religion”

Landenweb

[25] Editors of the Encyclopedia (2022) “Bavarians"

Encyclopedia of World Cultures

[26] Giotto (2022) “Viking Invasions of Europe”

University of Penfield

[27] Rachael Bletchly (2014) “The truth about Vikings: Not the smelly barbarians of legend but silk-clad, blinged-up culture vultures”

Mirror

[28] Editors of Scandinavia Facts (2022) “Why Did the Vikings Attack Monasteries? Get the Facts”

Scandinavia Facts

[29] People living in what is known today as Caucasus

[30] Wikipedia contributors (2022) “Avars (Caucasus)”

Wikipedia

[31] Wikipedia contributors. (2022) “Bogomilism”

Wikipedia

[32] Shahan Garo (2019) “The Remnants of Caesar’s Civil War: Naval Battle off Tauris Island”

Tldr History

[33] Editors of History Guy (2022) “Charlemagne, King of the Franks”

History Guy

[34] Ibid

[35] Carl Waldman, Catherine Mason (2006) “Encyclopedia of European Peoples”

Infobase Publishing. p. 200

[36] Editors of Divus Julius (2022) “The death of Christ on Holy Wednesday”

Divus Julius

[37] Alyson Horton

[38] ThoughtCo (2021) "How Is the Date of Easter Determined?"

Learn Religions

[39] Editors of Greek Boston (2022) “Greek Orthodox Holy Wednesday (Holy Unction) Religious Service Overview”

Greek Boston

[40] Editors of Wilstar (2022) “Orthodox Good Friday”

Wilstar

[41] E. Tylor (1889) “Researches into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Art, and Custom” Vol. 2

John Murray p.270

[42] Editors of Digital Maps of the Ancient World (2022) “Sol Invictus”

Digital Maps of the Ancient World

[43] Lilly Ross Taylor (1931) “The Divinity of the Roman Emperor”

American Philological Association p. 65

[44] James Eason (2022) “Sol Invictus and Christmas”

University of Chicago

[45] Toynbee, Arnold Joseph (2022) "Julius Caesar"

Encyclopedia Britannica

[46] Redactors ANSA (2020) ‘’Ossola festeggia a luglio il Natale’’

ANSA ViaggiArt

[47] L. Knight-Jadczyk, 2021

[48] Mert Toker (2019) “What historic/ancient civilization or society had the lowest preference for mercy?”

Quora